Archives of Personal Papers ex libris Ludwig Benner, Jr.![]() - - - - - -Last updated 5/29/17.

- - - - - -Last updated 5/29/17.

Project originally posted 2 Jan 98

| MODEL OF HUMAN DECISION PROCESS FOR ACCIDENT INVESTIGATORS |

The Model

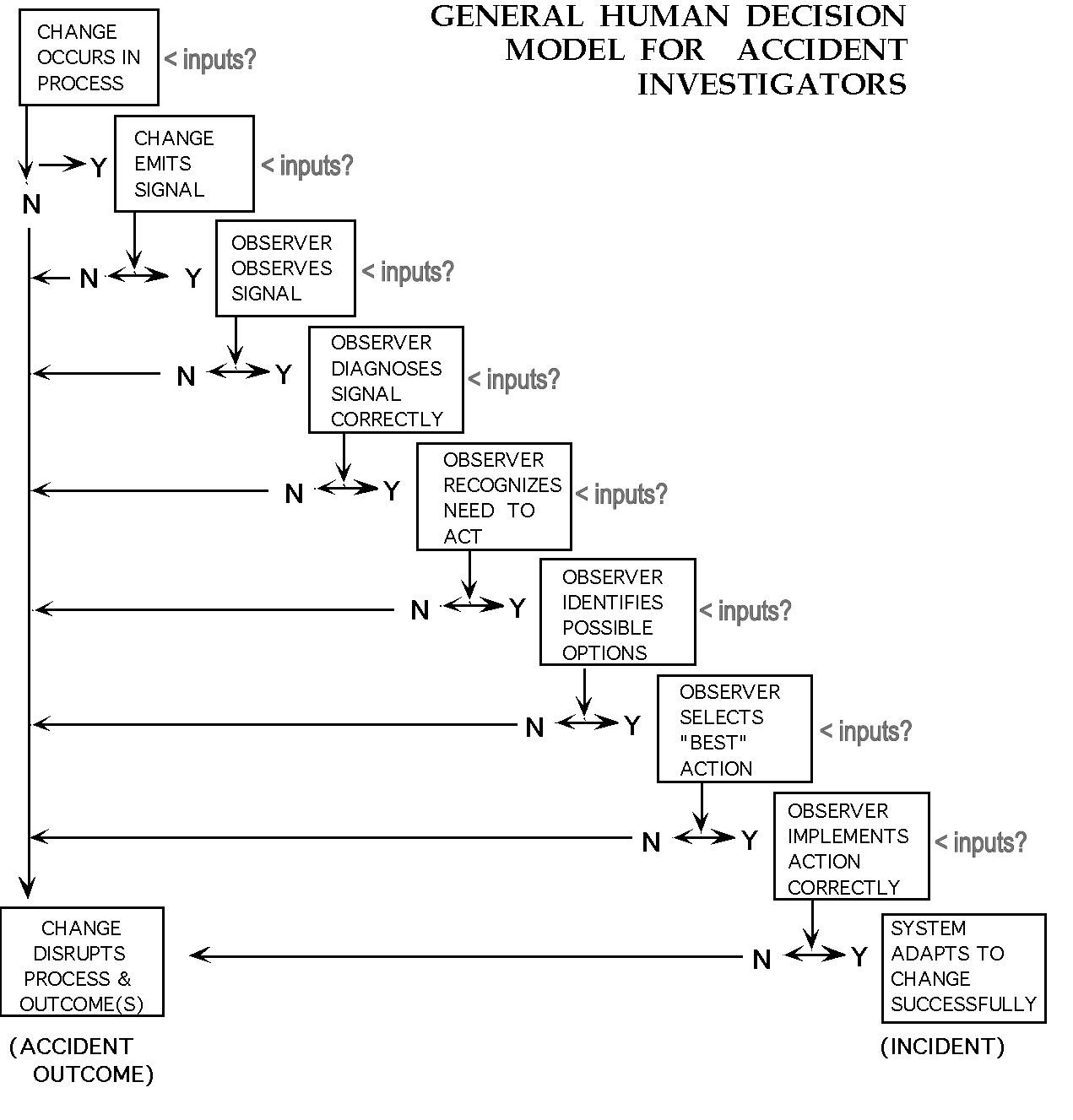

Making a decision is a process. This process has many common elements, whether made by people or objects. This model flow charts the general human decision process elements involved in accidents. The purpose of this model is to identify behaviors to change or emulate to reduce future safety risks. The model flow charts the general human decision process elements involved in accidents, in the sequence they must occur. Accidents are aborted when the decision maker acts to bring the process to the no-accident outcome in an orderly way. The model was developed by integrating observations during interviews with witnesses during accident investigations. Guidance for applying the model in investigations follows the model.

![]()

Applying the

GENERAL HUMAN DECISION PROCESS MODEL

FOR ACCIDENT INVESTIGATORS

CAUTION:

DECISION ELEMENTS MAY BE AFFECTED BY CONCURRENT EVENT(S) DURING EXECUTION

For preparation, purge your mind of cliches and abstract words and phrases used in the "human factors" domain, and focus on describing concrete actions reported by the individuals you are interviewing in the form of building blocks described at http://www.ludwigbenner.org/manuals/MESGuide00.pdf. Let analysts and others attribute their characterizations during their analyses of the descriptions you develop.

This Model describes the general decision making process faced by individuals while interactions are occurring among people, objects and energies during any kind of accidental occurrence process. The model helps investigators discover and define changes, signals they emit, their signal detection, diagnosis, and decisions made during the process, and the outcomes of those decisions and actions they produce. At each step, be alert for both unsuccessful AND successful decisions and actions to emulate..

By investigating influencing actions by manageres, supervisors, trainers, designer, procedures writers, policy creators and any other programmer source's influencing input actions related to each of these elements, investigators can link specific prior actions to each element. The linking task and necessary and sufficient logic test for each entry's inputs are indispensable to assure discovery of all interactions.

This tracking of each decision process element enables investigators to define specific relationships or links among actions as problems or needs arise. It then enables investigators to pinpoint the places to look for concrete actions (behaviors) that will change future performance, rather than describing problems and needs in subjective, ambiguous or abstract characterizations as "human factors" terms such as errors, failures, causes, malfunctions, vigilance, attention, wrong, unsafe, skill errors, latent failures, active failures, etc.

To apply this Model during investigations or interviews, identify people who appear to have had a role in the incident process, or may have observed those people's actions. Then begin to look for changes in the process or its environment that would have created an original need for decisions and action by some person (or object) to keep the process progressing toward its intended outcome. Determine the the extent possible the inputs which influenced each decision and action step. Then follow the same procedure for subsequent decisions and actions until the occurrence is understood.

When you identify a change or perturbation, determine if it emitted or displayed some kind on signal, active or passive, that the person could have noticed. If it didn't explore why it didn't and what effect that had on the outcome.

If the change or perturbation did emit a signal, determine whether the person saw, heard, felt or otherwise "observed" or captured the signal. If not, explore why not, and what effect that had on the outcome. If observed, try to understand why also.

If the person observed the signal, was the signal diagnosed correctly, in the sense that the person was able predict or anticipate the consequences of the change from the signal and their knowledge of the system operation and functions. Explore why or why not, and the effects.

If the anticipated consequences of the change were correctly identified, did the person recognize a need to do something (act) to intervene and counter those consequences? Again explore why or why not, and the effects.

If so, did the person identify choices for action that were available for successful intervention? Was this a new situation were the action had to be devised, or was this something that prior experience or analyses or training anticipated and provided "cook book" responses to implement? In other words, was the person confronted by an adaptive or habituated or no response decision? (To this point, you are asking primarily for observations during an interview. Here, you may begin to get into personal judgment issues, so explore this area with empathy toward the individual, particularly when faced with an adaptive response.)

If any response actions are identified, did the person chose the"best" or a timely effective response to implement? Explore why the response was chosen, or explore why none was.

If a potentially successful response was chosen, did the person successfully implement the desired action? Explore why or why not and how success of any intervention was monitored or can be determined. .

If a suitable response was implemented, the system may have adapted to the change without an accidental loss or harm, unless other changes occurred, which restart the decision process. If the response did not achieve a no-accident outcome, explore why it didn't. Often this leads you to discovery of invalid system design assumptions or other design problems.

After working with this model, investigators are in a much better position to describe and explain what happened when so-called "human error" or"failure" is alleged. Investigators will also be in a better position to identify concrete actions to improve future performance of that system.

The model and its implementation will continue to evolve as new insights and demands surface.

Source: Created 1976 by Ludwig Benner Jr. First published in FOUR ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION GAMES, Appendix V-F, Lufred Industries (now ludwigbenner.org) Oakton, VA 1982 and requently updated as new insights become available.

Contact: Ludwig Benner, (luben) for support at ludwigbenner.org

![]()